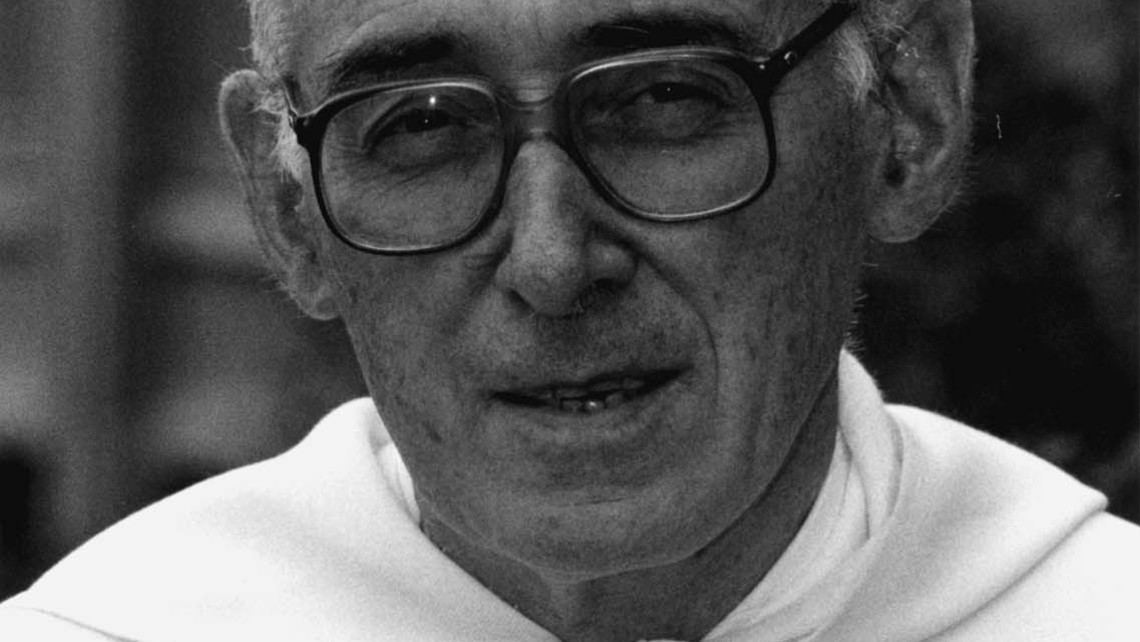

The late Father Servais Pinckaers, O.P., was a Belgian Dominican described as one of the leading moral theologians in the Thomist renewal of moral theology after the Second Vatican Council. His work helped to restore the field of moral theology from its reduction to a summary of principles and case studies in manuals, to a more lively discipline which integrates the moral life into the rest of the spiritual life in a manner faithful to St. Thomas Aquinas’ method.

As part of his project, Fr. Pinckaers does a “post-mortem” on the development of moral theology to identify how the field became reduced to a study of manuals. He finds that moral theologians were influenced by some of the same mistaken notions as Western society, particularly in the way that freedom was understood. He describes the choice between Thomism and Western society’s view as a sort of tale of two freedoms: Freedom for Excellence and Freedom of Indifference.

Freedom for excellence is the classical view of freedom, which largely predominates almost since the time of Plato and Aristotle. It presupposes that man is naturally ordered to choosing the good and so he has the capacity to act with excellence as he wishes. This freedom indicates that free will arises from the faculties of intellect and will and from a natural longing for truth, goodness, and joy. Freedom is present in germ in children and develops through education and practice of the virtues until it flourishes in maturity. It unites one’s actions into an ordered whole that nourishes human flourishing with its end in authentic human joy.

Freedom for excellence was embraced and Christianized at the very early stages of the Church because it conformed so well with revealed truth. In fact, Christian teaching greatly strengthened the classical understanding of freedom and virtue. The fall from grace and the dis-integration of human intellect, will, and affects (i.e. appetites and emotions) explains why we experience conflicts in choosing authentic goods. It also confirms the universal experience that when apparent goods (most often, sensible goods) are chosen at the expense of the authentic good (i.e. the true, common good to persons), freedom to choose is lost and replaced by enslavement to the poor choices.

Choosing apparent goods at the expense of authentic goods results in momentary pleasure, but the experience eventually gives way to problematic results such as the loss of self-mastery and self-possession, the acquisition of bad habits, vices, and addictions, as well as physical and psycho-emotional pathologies, and moral decline. Christian teaching of our renewed access to sanctifying grace in and through Christ and our need to cooperate with this grace helps to explain the great capacities of the Saints to exercise tremendous self-control, to demonstrate consistently heroic moral lives, and the ability to experience joy in even the most difficult of physical and emotional circumstances.

But in the 14th century, speculative thought arose which divorced happiness from the moral life. William of Ockham, a Franciscan theologian, introduced his Ockhamist Nominalism that was to have a devastating effect on all aspects of thought, religion, and society; a devastation we still suffer from today. Ockham originally set out to rescue God’s omnipotence from what he mistakenly saw as threats posed by St. Thomas’ integration of Aristotelian metaphysics into Christian theology. In the process, he tore asunder the metaphysical structures of realism. He denied the reality of universals (i.e. natures), arguing that God did not need what St. Thomas called the divine ideas in which all created entities participate. Rather, Ockham argued that God knew everything as an individual being, rejecting Thomas’ doctrine that what we call a nature (e.g. human nature) had any reality.

This led directly to Ockham’s voluntarism. If God has no nature, then He is pure will. For Ockham, God can’t be limited by anything, including a nature. Ockham says that God can change His mind and He can even choose contradictions. One example he provides is that God could command man to hate Him and if He were to do so, then it would be a sin to love Him. Love can no longer define God’s nor man’s nature. Ockham’s via moderna also had a seriously damage influence on our view of creation. Creation no longer must be good, it no longer had to reflect God’s perfection because creation arises from an arbitrary, albeit divine, will.

Ockham reverses the traditional relationship between freedom and nature. For him, freedom precedes nature, or what he is willing to call nature. Thus, free will precedes reason on the level of action and so will is the first faculty of the human person. He defines freedom as the power to choose indifferently between two contraries. Because free will is first, one can choose between being happy and not being happy. There is no natural inclination to happiness, it is a matter of indifferent choice of the free will. Nature no longer orders freedom or happiness; rather, the good is found in the choosing. This is the freedom of indifference.

There is no longer a connection between the freedom of God and the freedom of the human person. We cannot discern good choices by understanding God and human nature. We are now reduced to obligation imposed by the law. The law becomes juridicized and is increasingly seen as arbitrary. Because happiness is divorced from nature, happiness must be redefined. Happiness is now assumed to be achieved by freely choosing. Therefore, obligation to follow law means that happiness sometimes has to be sacrificed to obligation. Obedience to the law is emphasized and moral action as a response of love with a goal of happiness is pushed out of view. This Nominalist thinking gave rise to a morality of obligation. Law now is viewed as a necessary evil, rather than a guide to how to fulfill human nature. Ockaham’s view of freedom was accepted by the Protestant Reformers and institutionalized by philosophers like Immanuel Kant and his ethics of duty. Freedom of indifference forms the predominant view of freedom influencing the modern West.

The consequences of Nominalism and the primacy of the will together with the denial of nature and the rebellion against authority gave rise to modernism, but their logic resulted in post-modernism. The ethics of obligation has been rejected in the post-modern, radically individualist mindset. Because there is no human nature to which to conform in order to achieve happiness, it has become a largely unachievable goal. Therefore, the goal of achieving happiness has been replaced by the pursuit of sensual pleasure. The only moral absolute remaining to postmodern minds is the primacy of choice. When choice is king and there is no nature to guide one’s actions in the way of right and wrong there is no limit to actions which can be justified. This helps to explain how society has come to be able to justify killing our unborn, glorifying sexual and alimentary hedonism, and redefining human nature to accommodate any number of disorders we now euphemize as different sexual orientations or diversity of genders.

For Christian traditions that were founded on Nominalist metaphysics, man is totally corrupt and there is no possibility of a freedom for excellence. For nihilistic, post-modernism there is nothing to perfect except social structures dedicated the cult of choice. Unfortunately, Catholics often fall into this disordered thinking. To this Pinckaers responds that the need is great to rediscover and renew the understanding of the freedom for excellence to which the Holy Spirit constantly beckons us and offers us the grace to pursue and achieve. Excellence is what the human heart was created for and it is the only true path to human happiness because its end is Christ.